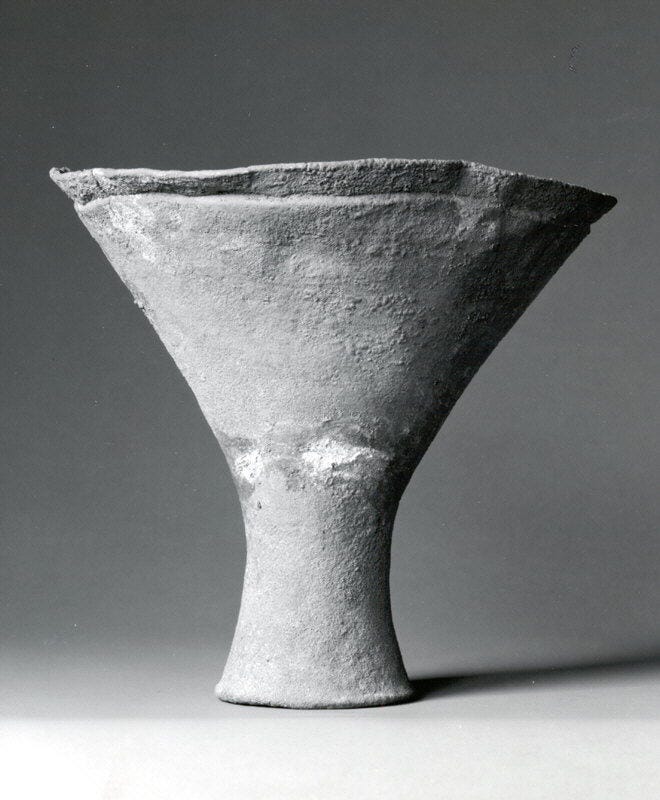

Metropolitan Museum The Collection Ancient The middle sector is the artist’s focal point in this sculpture from the Bronze Age, raised from below and burdened from above – Public Domain

Can progress come about without individualization?

Originally published on Medium May 22, 2020

Prior to the 1930s when Australian archaeologist, V Gordon Childe, presented his theory about the metal-smiths of the Bronze Age and their concomitant relationship to the power elite, archaeologists considered craft-making merely as a result of economics. Childe identified the powerful role that prestige goods played in the early development of craft specialization and connected the emergence of craft specialists with an itinerant metallurgist culture in prehistoric Europe. A debate emerged around the social and political role that specialized craft production played in the structuring of prehistoric culture, not unlike the role that digital invention plays in reshaping the world today.

Rooted in Movement, Aspects of Mobility in Bronze Age Europe, an introduction published by the Jutland Archaeological Society, Constanze Rassmann quotes and contests Childe as he hypothesizes that the traveling metal smiths enjoyed a great deal of individual freedom:

“But if they were detribalized they were ipso facto liberated from the bonds of local customs and enjoyed freedom to travel and settle where they could find markets for their products and skill” (Childe 1940, 163).

Rassmann dismisses Childe’s interpretation, implicating that there is nothing to support it except for the evidence that metalsmiths traveled around Europe during the Bronze Age. Rooted in Motion (the introduction), as the title suggests, develops an evidentiary theory that the craftsmen were not free agents but either attached to elites who financed the crafts productions or other social structures “rather than being socially independent, as suggested by Childe (Childe1940, 163).

However, Rassmann then goes on to relate the “the regular craftworking movement” model, in which itinerant smiths had seasonal dwellings in villages that could not sustain a full-time metal worker. This model can also support the concept of the metal worker as a free agent, which is not likely to leave as many traces as a larger social group.

A persistent characteristic of centralized societies is the attitude that nothing exists outside of it, but someone always exists outside of the dominant culture, be they the lone individual, the homeless, the underground, the resistance, the black market, the occult, the free enterprise system, or The Mists of Avalon. Why should it have been different in prehistory?

An elegantly proportioned copper alloy spearhead-cyprus Public Domain

Archaeologists debate whether specialized Bronze Age craft-making was a full-time activity or whether it was done in conjunction with other activities. Based on the amount of time, the specialized knowledge, and the raw materials needed to support specialized craftsmen, archaeologists reason that full-time metalworkers could only have existed in a surplus economy where there is production beyond what is needed for sustenance. It is theorized that specialized craftsmen arose in tandem with a powerful elite class for whom the craftsmen produced their work as objects signifying the elite status of the wearer or owner. Crafts, identifiable as produced by a single craftsman or workshop, have been found in remote regions spurring speculation that the craftsmen themselves were “prestige goods” exchanged among palaces and whether the craftsmen themselves were members of an elite class, much like the celebrities of today (Rooted in Movement, Aspects of Mobility in Bronze Age Europe by Juteland Archaeological Society).

Childe’s ideas about the emergence of specialization among a class of metalsmiths roaming across Europe have been challenged within the archaeological community but the hypothesis that specialization would have affected social and political class structures is widely accepted, with specialization implying that the craftsman’s time was not subsumed by providing food on the table, and a roof over the head, subsequently establishing a different class of people conducting a specialized activity during prehistoric times.

In Approaching Specialisation: Craft Production in Late Neolithic/Copper Age Iberia, author Jonathan T. Thomas asks which came first the chicken on the egg? Specialization or a more complex society? He concludes that the relationship between the chicken and the egg may be mutually recursive:

However, by momentarily turning this view of specialisation on its head, we can see how the development of expertise connected to the use and efflorescence of prestigious types of material culture may in fact have had a reciprocal or recursive relationship with the evolution of socially complex groups. Approaching Specialisation: Craft Production in Late Neolithic/Copper Age Iberia, by Jonathan T. Thomas

Prestige Goods: Bronze Age Central Asian Beaker with Birds made out of Gold Alloy https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

I submit that specialization devised at an individual level had to come first because the elite investor does not know how to invent or make things as is exemplified in contemporary times in the recent Elizabeth Holmes saga, wherein Holmes imagined highly marketable science fiction in the form of a blood test requiring only a pinprick of blood that would diagnose practically any ailment. Although Holmes attracted nine billion dollars in investment from the highest strata of the power elite and maintained a highly staffed, state-of-the-art laboratory, it was not enough to create the technology out of thin air. The seed of a viable technology has to exist first, after which a reciprocal and recursive relationship can promote further development.

In the twenty-first century, that seed is classified as intellectual property.

The American Idea

As I was reading these papers, I observed the missing mention of property rights and realized that it would be difficult to piece together how that happened during an ancient time when writing did not yet exist. States and property rights were emergent during the Bronze Age age, the one being dependent on the other. It is reasonable to hypothesize that before states and property rights were formed, the seeds of all later formulations were already latent within human culture.

The American Idea is founded on individualism, from which the rights of property arise, as aptly expressed in the words of James Madison: These words go straight to the social and political function of specialized skills, and the development of a complex society:

The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to an uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. James Madison, Federalist Paper # 10

Utility Item, metal, Bronze Age Central Asia, Public Domain Image

Other craftsmen whom archaeologists call “subsistence craftsmen” are thought to have made tools that were commonly used, and to work on-demand on a seasonal basis or even develop products sold in a market, as independent entrepreneurs.

American archaeologists Edward Shortman and Patricia Urban speculate in Modeling the Roles of Craft Production in Ancient Political Economies, that some of the subsistence craftsmen class developed an income level beyond mere subsistence to occupy a middle economic class marketing to its own peer group, but, to date, I have not found archaeologists giving this group its own identifier, diminishing its significance. However, Modeling the Roles of Craft Production in Ancient Political Economies brings home a distinctive social value in producing for peer markets

These crafts, in short, fall at opposite ends of the continua outlined in Table I from prestige goods production processes, yielding utilitarian items, not wealth (White and Pigott, 1996). Raw material, labor, and skill requirements make such activities relatively open to all while aspects of demand and distribution ensure that craftworkers exercise considerable autonomy in pursuit of their own agendas(Hagstrum, 2001). To be sure, paramounts may benefit from these transactions and manufacturing activities through, say, taxes levied on market exchanges (Morrison and Sinopoli, 1992; Sinopoli, 1988). The point, however, is that control over production, consumption, and distribution is vested in non-elite hands

When reading the interpretations that archaeologists derive about human society by examining ancient artifacts, one must remember that it is reasoned speculation about a distant time from within our own time. I find Modeling the Roles of Craft Production in Ancient Political Economies, the most interesting paper of those I have explored because it describes what sounds very much like a middle class in prehistoric times without ever giving that class an identifier. Archaeologists often construe prehistoric culture as a two-tier class structure made up of the elites and the commoners. A middle sector, which Shortman and Urban flesh out, remains generally classified as commoners, even as Shortman and Urban observe that there are classes within the commoners and that there are multifarious forms of the elite, recognizing that different cultural specializations have their own elites.

Without intending to distract from Shortman and Urban’s fluid thinking about prehistoric culture, it is in itself politically significant that a culture sounding like a middle class was not given an identifier beyond “commoner”. This linguistic shortcoming plays into wealth inequality as a central issue throughout history. If wealth inequality is not to be the dominant economic structure, then the middle must have significance, worthy of identification of importance.

Midcentury bowl in variegated moss green bowl by Andersen Design

Back to the future past, in the twentieth century, I was raised in a business in a home that designed and hand-produced ceramics. When Andersen Design was established, the existence of an abundant American middle class was the social structure that made the business concept viable. My parents followed their own inspiration, authored their own product ideas, specialized in developing original glazes and decorative techniques, and used the hand-crafted slip-cast technology to create a product affordable to the middle class. That, in today’s parlance, is our brand identity.

Training was done on the job but the techniques used, are not those of unskilled labor. The variegated glazes and fluid decorating colors involve skills uncommonly used in production because interactive materials produce unpredictable variations, categorizing the production as an art form. Specialization is not in materials sourced in remote regions of the world, or even a state-of-the-art studio, but in the individual artist’s relationship to the process. Archaeologists establish the traveling culture of prehistoric artisans through the idiosyncrasies of the craftsman’s hand, those same individualized subliminal choices are part of a total interactive process when working with fluid materials, which in the case of our company, have always been sourced in the USA, with an exception for an occasional oxide.

Midcentury Fin Whale by Weston and Brenda Andersen for Andersen Design

Archaeologists have a propensity to tell a story from the perspective of large social organizations, the context in which the individual exists. From the perspective of individual creativity, the social-political role of Bronze Age craftsmen is similar to that of contemporary designers. Perhaps a design begins as a solution created for personal use and then becomes a product concept. An individual entrepreneur might work a part-time job until the business is established, or just take the leap as my parents did. The solid financial establishment did not come immediately for them but required steadfast commitment through challenging times. One can also take the path of the widely written-about start-up company, which falls into the prestige goods pattern of development, wherein the author may not remain in control of his own design or even his own company.

An alternative social-economic structure in which crafts were produced is historically called “cottage industries”, which means work that was done in a home environment. Archaeologists refer to crafts made in a home environment as subsistence production and reason that since it was combined with other activities and not a full-time activity that specialization cannot develop in such an environment.

By definition, the best environment for specialization will vary across fields of specialization and so broad assertions do not apply to a generalized category, “specialization.” My experience is that it is not the number of hours one works per day but the consistency with which one practices a skill that hones it. The ability to balance different activities can be beneficial as a holistic process of living while earning a living.

In response to coronavirus, many corporations are realizing that they can work with people in their own spaces while saving money on renting large offices. This will have an effect in many contexts as the civilized world reinvents itself. It will be an interesting time.

Afterward

I completed writing this piece, or so I thought and I went down to the shoreline and watched the waves splashing against the rocks, and then I turned and saw a creature, most, divine, whom I had always wanted to see but had never before had the pleasure. There it was, a Bald Eagle, an iconic symbol of American freedom. It was perched on top of a tall pine tree behind me, like this:

Bryan Hanson Unsplash

I watched it for a while, hoping to see it fly but it was sitting on the top of the tree for a very long time, turning its head and looking all about before it finally took off flapping its wings over the water, and then gliding on the air currents. It flew off into the distance and then turned around and flew back to perch on top of the tree again and as it did so it glided directly over my head like this:

kameron kincadeunsplash

The Eagle took flight and returned to its perch three times. On the third time, I lost sight of it over the water and started walking back when the eagle returned a fourth time and took perch on a different tree which was now directly in front of me so that I could get a better view of it, close enough to see the variegated colors on its breast.

Occasionally it would look down on me. It felt as though the eagle was performing for me as it kept taking off and flying around the tree and returning so that I saw many views of it in flight. My favorite view is when it comes in for a landing with its claws dangling down, like this:

Richard Lee-Unsplash

After a while, It flew away and I walked on and saw it return one more time to land on a more distant tree so that I could see its regal form in silhouette. It was still there when I drove by on my way home.

Mark-De-Jong — Unsplash

To sight a Bald Eagle for the first time at this particular moment was very mystical in feeling as if to say, now is the dawning of a new American Age.